The word “drawing” brings up a sense of anxiety to some people. Mostly because they fear they can’t draw. But what if the purpose of the drawing is to express anxiety? Drawing has the ability to go far beyond the representation of things. Learning how to draw objects so that they are recognizable is exciting and satisfying. But that is not the only thing you can do with drawing. Drawing can be used as way to reveal human feelings and a range of emotions. Drawing as expression can transcend language. Drawings can be awkward, messy, imperfect and still be really good drawings. The drawings of Rashid Johnson (1977-) began as representations of figures but developed into expressions of a vital and raw anxious energy. Johnson even titles some of his works, Untitled Anxious Drawings, leaving the viewer no doubt about his main subject.

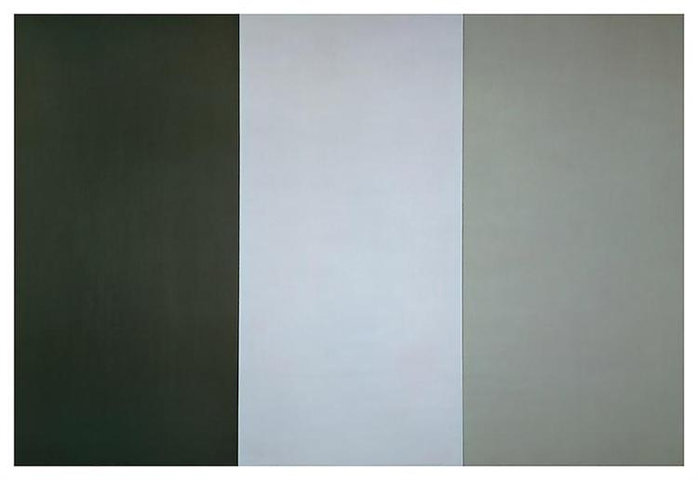

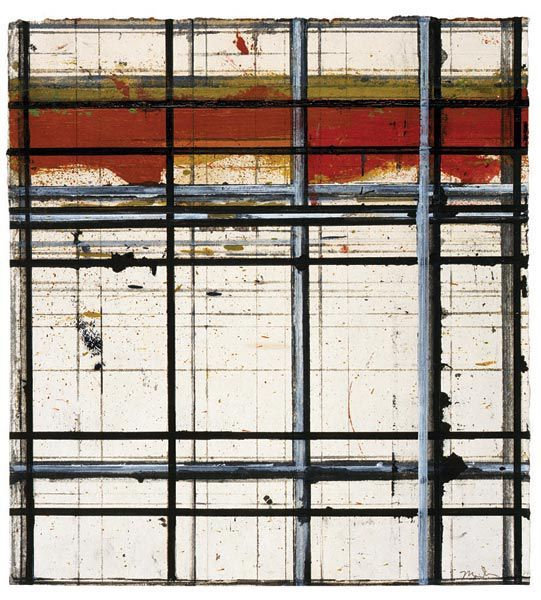

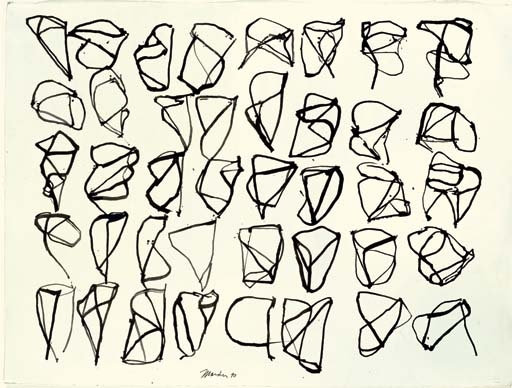

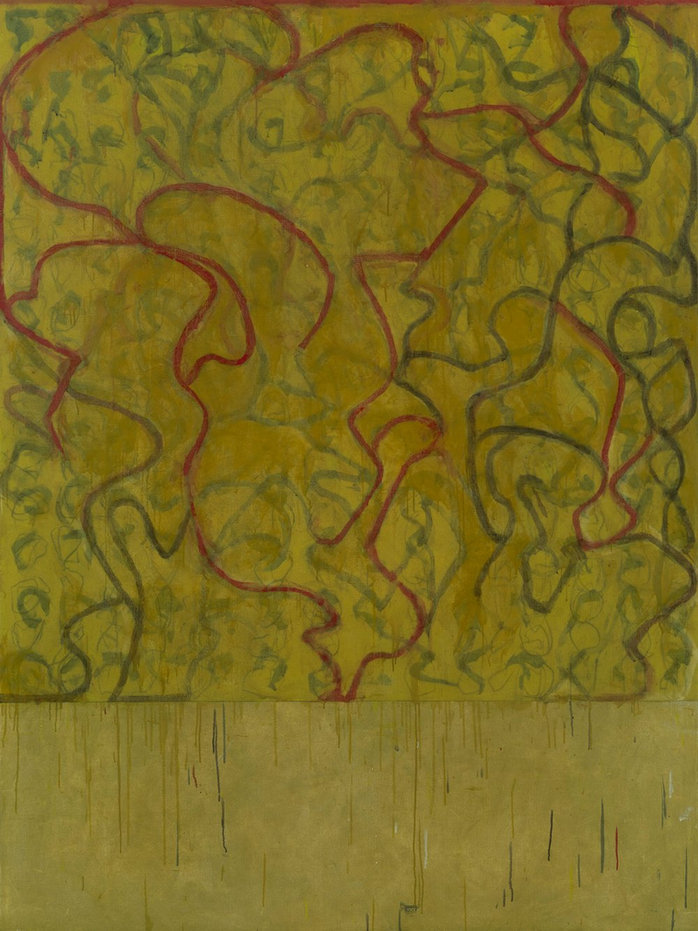

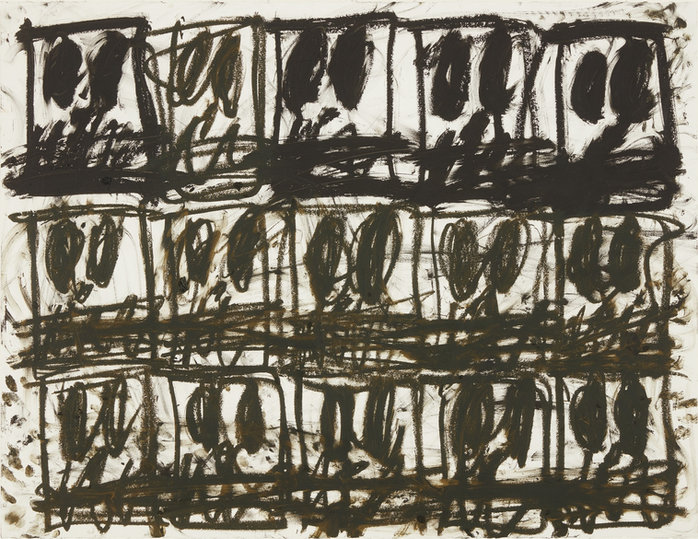

In 2015 Rashid Johnson began his “Anxious” series by making singular portrait drawings called Untitled Anxious Man and then the portraits became grouped and called Untitled Anxious Audience (image above) and then just Untitled Anxious Drawing (see below). The first drawings were made using melted black soap and wax, materials used by the black diaspora in their everyday life for cleaning and grooming. Johnson enjoyed the idea of soap as a material associated with cleansing, as well as the irony of the soap being black and related to dirt, or things that are considered unclean. Lines are scratched into the soap and wax with a sharp tool creating a graffiti-like appearance on the tiled surface. The use of ceramic tiles references a place of refuge for Johnson, the Russian and Turkish Bathhouse in New York. Your first thoughts when looking at the above drawing might be to think it is messy, childlike, violent, even visually unattractive. And yet as human beings we have all felt something like the emotions that this piece conveys: anger, frustration, confusion and excitement. Johnson wants you to get past what you see and to think about what these drawings make you feel.

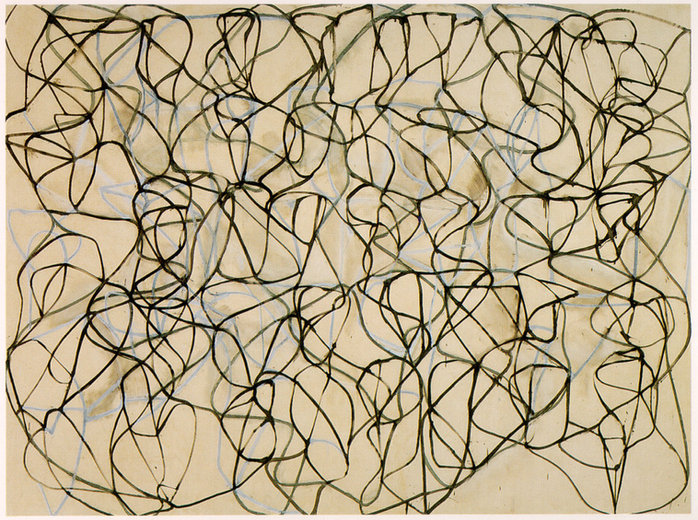

The Anxious Drawings began to take on a more abstract, almost cartoon-like feel and yet we can still recognize the vestiges of a human face. Johnson describes his drawings as being “representative of many personal and collective anxieties: becoming a father, inequality and racism, and an collective sense of uncertainty in the world.”

During the pandemic, Johnson began using the colour red to depict a sense of urgency and the faces started to dissolve even more into the material. In this CNN article Anxiety is part of my life (which includes a short video), Johnson discusses what it was like to make art during the pandemic. He describes the period as “‘an incredibly difficult time. It feels simultaneously unsettling, urgent, and radical.’” The Anxious Drawings always start with a random light scribble that covers the surface, almost done as a way to release the first burst of anxiety prior to getting further into the subject of the drawings.

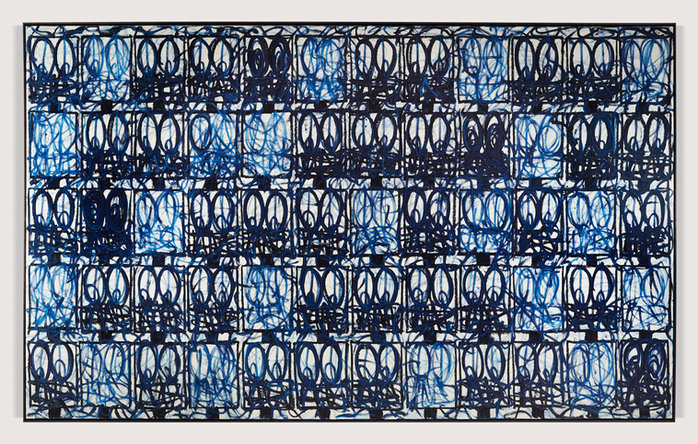

Johnson’s recent work was part of an exhibition called “Black and Blue”, a title that has multiple meanings from a “bruise” to being a black person who is feeling blue such as in the song of this title a by Louis Armstrong.

From the David Kornasky Gallery press release:

Johnson’s drawings contain vocabulary that is abstract, the representational, and conceptual, challenging the notion that these can be understood as separate categories. The grids of faces embody, on the one hand, the freneticism of intense psychological response; on the other, though, they reveal roots in non-objective minimalism. As such, they are vehicles for both internally and externally oriented modes of awareness.

For more information and a video of Johnson talking about this work: Black and Blue. The artist’s CV as well as several articles on Johnson can be found on this page: Further Reading

These works that blur the lines between drawing and painting are often made without a brush, the marks are made mostly with the artist’s fingers drawing directly on the canvas or paper surface. The works are frenetic and calm. The wild gestures contained within the grid contrast freedom and containment. The lines between anxious mark-making and energetic excitement become completely blurred. These intimate and expressive works investigate the anxiety of the individual and the collective.

For additional viewing:

Rashid Johnson CNN Interview

Rashid Johnson on Success and Healing

Rashid Johnson Soldade

Rashid Johnson Artist Talk